After her

suicide attempt, we found

Martha at the

hospital, locked

up alone in

a small room with big

windows so she

could be observed continuously. She wore a

hospital gown and had nothing in her room but a bed, her

Bible, and a cup of ice water to relieve the burnt tissues of her throat.

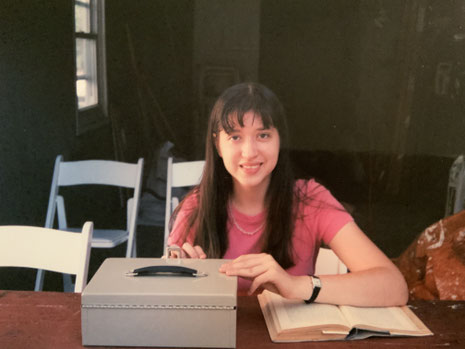

Martha at sixteen in summer 2010, running the desk at our tag sale.

She had had her stomach pumped, after which she had torn out the IV from her arm, spilling blood, and tried to escape. That was why they had had to put her under lock and key. She waved to us when she saw us through the glass and hugged us fervently when we were allowed inside.

Martha wanted us to take her back to CTY so she could rejoin her friends in the college library, but we had to tell her that was not possible. Under Pennsylvania law, it seemed, a person who had attempted suicide had to be involuntarily committed for a time. Martha was horrified. “If I’d known that I wouldn’t have attempted suicide!” she said.

I couldn’t get a clear picture of why she had attempted suicide. I knew she had been sad about losing Ying and betraying Aleksei, so maybe she had tried to kill herself to avoid further pain. But it also seemed that Aleksei urged her to do it, perhaps so she could join him. Later in her diary, she wrote to Aleksei, “You tried to drive me to suicide; admittedly it did not seem like a bad idea.”

I wondered also why I had not perceived that she was in danger of suicide the night before the attempt, when we talked on the phone. I had known she was depressed but somehow I hadn’t thought her life was threatened. I didn’t understand her, and it had almost cost her life.

That night, the paramedics put Martha on a stretcher and took her by ambulance to a mental health facility for young people called KidsPeace. Melinda accompanied her in the ambulance and I followed by car, though I lost the ambulance on the dark highway and had to figure out the rest of the route from directions I had gotten. Martha stayed at KidsPeace for a week while Melinda and I stayed in a hotel nearby, visiting her every day.

During her days at KidsPeace, Martha was more depressed than she had ever been in her life. Her throat burned for days because of the laundry detergent she had swallowed. In her diary, she called herself a slut for having run off with the first person who read Nietzsche. She envied the juvenile cancer patients she saw around her at the institution. She called herself weak for not having died. “They didn’t fucking save my life,” she wrote of the hospital. “I saved it myself through my weakness.” She hated that, by her own hand, she had lost her last week of CTY, her last chance to be in Ying’s company.

Martha looked desolate every time I saw her at KidsPeace. She wore black clothes and flip-flops, because shoes were not allowed. Sitting with her on a sofa in the visiting room, I suggested she and I make a pact not to commit suicide. She agreed. For the rest of her life, to keep that pact, I put suicide out of my mind.

###

When Martha returned home, the world seemed bleak to her. She described it as wandering in the desert of the real, a phrase she had picked up from The Matrix, a movie I’d shown her. She didn’t have Ying and she no longer believed in Aleksei. She had, she wrote, “essentially invented a lover so I could have someone to love.” In place of love, she devoted herself to knowledge for the rest of the summer. She studied theology, philosophy, history, geography, psychology, literature, Spanish, French, German, Russian, Latin, mathematics, science, art history, politics, economics. She read The Genealogy of Morals, The Interpretation of Dreams, The Tempest, Anna Karenina, the Iliad. She worked on writing a novel called The Lost Lake, a story she would later incorporate into a projected cycle of novels set in a fictional country called Logia. One weekend we ran a tag sale at our house, selling some of her old toys and baby paraphernalia, and Martha sat at the front desk, reading between customers.

One of the conditions of Martha’s being able to leave KidsPeace was that she had to acquire a talk therapist. So Martha started seeing the therapist who had helped me several times, Ella. Martha saw her weekly for the rest of her life, in addition to her regular visits to her psychiatrist, Dr. Abrams.

In September, when Martha returned to school, she so hated it that she told us she wanted to drop out. We talked her out of it, but barely. She seemed to me a bipolar basket case, always leading us to some new dimension of her disease. I couldn’t even trust that I’d find her alive when I got home, or that the next call wouldn’t be the one giving me the bad news. At least in the summer, Melinda (who had become an English professor at nearby Mercy College) could stay home and keep an eye on Martha. But now that it was fall and Melinda was teaching, Martha was sometimes all alone. We talked about hiring some kind of guardian for her to keep her from committing suicide, but since she was sixteen and too old to have a nanny, neither we nor Martha liked the idea.

Martha thought of herself as a drain on society—her family, school, and country. “Why don’t they exterminate people like me?” she wrote in her diary. “What good is a person with a debilitating chronic illness?” Nevertheless, she kept getting all A’s at school, sometimes all A+’s. She couldn’t help but excel, no matter how bad she felt.

While she was at school the hours crawled. School took “all the insanity” out of her, she complained. Some mornings she was so depressed she couldn’t make it through the day. Instead she would go to the school nurse, who would call me and ask if Martha could go home due to depression. I always said yes. A few minutes later Martha called me from outside school, on the cell phone she had started using, and for the duration of her walk home we talked about her feelings, she treading the sidewalks of Dobbs Ferry while I sat in my cubicle in Manhattan. Once she talked to me about how she had no one to sit with at lunch; she belonged to none of the groups and had to sit at the edge of a table where no one spoke to her. We discussed having her eat lunch at the Dobbs Diner reading a book. “As long as you have a book, you have a reason to be alone,” I said. I don’t know if she ever tried that.

“Since July 11,” the date of her suicide attempt, she wrote, “my life has been aftermath.” She was over Aleksei, but she kept pining for Ying. “If I live a hundred years I will never get over you,” she wrote to him in her diary. “I never loved Aleksei as much as I love you now.”

Death attracted her. “I want to die,” she wrote. “I wish I were dead.” But she went back and forth on the subject. “Sometimes I want death and sometimes I fear it but I am never neutral towards it. My spirit is resilient. I thought I would die when I lost them both but somehow I was able to bear it. I thought I was weak but I am actually strong.”

Now that she had lost her belief in Aleksei, she lost her belief in all disembodied spirits, including God. I had discovered Epicureanism since becoming an atheist and had discussed it with her, and she borrowed that philosophy for her own atheism. “I have an Epicurean reason not to kill myself,” she wrote. But she also wrote, “The universe should be destroyed.”

Writing fiction offered some relief. She wrote more fragments of the stories she would soon organize into her Logian cycle. She wrote a poem called “Love Poem to Death” that ended:

Possess me, ruin me, do not forsake me

Death, my lover.

Not only was Martha crazy, she was an adolescent, and with the two in combination she pushed us away. She blamed us for her troubles, identifying June 3, 2009—the day she told us about Aleksei and I demanded she see a psychiatrist—as the start of her decline. She sought the company of friends other than us—which I was glad about, except for the way she froze us out. Meanwhile, she was content to take our money and let us drive her places and bail her out of things.

The family was dysfunctional in other ways. I too was crazy, and Melinda, resoundingly sane, had no clue what was going on in either my mind or Martha’s. Melinda lived in an ordered world of gardening, going to church, and teaching classes. She faithfully served Martha and me with tasks like cooking and laundry, services we often took for granted because we were so preoccupied with our internal woes. Meanwhile, Melinda could get no inkling of what those woes were, no matter how much we talked about them. From her questions about my depression, I got the sense that she thought it must be a physical pain, like a headache. The idea of emotional turmoil, let alone metaphysical or religious turmoil, was as foreign to her as Uzbekistan. This created a divide between the insane, atheistic two-thirds of the family and the sane, theistic one-third.

The bond that had formed between Martha and me in her infancy had not entirely deteriorated. Whenever I came home from work, if she was at home too, she would stop what she was doing and come over to join me as I snacked in the dining room. She usually snacked too, cutting up a fruit or sharing my peanuts. We sat and talked about our days or the books we were reading. Because we were both crazy, we could share stories about our moods, our symptoms, and our meds. It was a sign of great love that Martha set aside this time for me every day. She wasn’t required to; she just did.

###

Dr. Abrams was stumped with what to do about Martha’s craziness. He declared she was not schizophrenic but seemed beyond bipolar. Nevertheless, in October, he put her on lithium, the classic bipolar drug that I also was taking. Ironically, as soon as she started lithium Aleksei reappeared. He was present again and she loved him just like before. “Lithium has brought me back to you,” she told him. She stopped pining for Ying and felt happy loving Aleksei, knowing he would never leave her. It was a peaceful happiness, she felt, not mania. “Let all my other beliefs and passions fade,” she told him. “I will always return to you.”

Having just become an atheist, she embraced Christianity again because Aleksei was a Christian. “If you are saved, I want to be saved,” she told him. “If you are damned, I want to be damned.” She also took up belief in the divine right of kings and the inferiority of women because he believed in them. The latter clashed especially with Melinda’s Gloria Steinem feminism. Martha feared that soon we would call Aleksei a symptom and try to destroy him. “I will wish to live so that they let me keep loving you,” she wrote. “You are the most reason I’ve ever had for wanting to live.”

For three weeks Martha and Aleksei were inseparable. She recommenced her Russian lessons to communicate better with him. When she said the pledge of allegiance at school, she put one hand on her heart but the other on her Russian dictionary. She longed to place her body in his arms after death. She hated our disapproval of him, hated how we and her doctors mispronounced his name. She saw herself as fighting fate to love him. We, for our part, as much as we disliked Aleksei, were glad she was feeling better and hoped it would continue.

But Martha’s love of Aleksei was never unalloyed happiness; it was always laced with grief because he was dead and not in physical reach. To express her mourning, she fasted between meals on Fridays, and secretly self-harmed by the things she ate—bitter seeds, sour fruits, spicy meats, jalapeño peppers.

She thought she wrote better the madder she became, and she might have been right. “The pen belongs to the mad, the intense, the insane.” Grandiose ideas filled her mind. “People like us live on a grander scale than others.” When the wind blew at her—which had always been a sign of Aleksei—she felt “the grandeur of love and of the universe.” When her love wavered, she fought to maintain it. “My problem is that I am not obsessed enough.”

Dr. Abrams recommended a consult with a neurologist to rule out neurological causes for Martha’s insanity. The day Martha saw the neurologist, she was upset because she had to miss an English class play based on The Stranger. By then she had read The Stranger and become interested in existentialism. The neurologist found nothing physically wrong.

In what would be a lasting image of herself, she compared herself to a supernova and the subsequent black hole. She was aware that a supernova was not only more brilliant than anything in the sky, but that it was generous and fertile, begetting elements that would otherwise never exist. She wondered if life itself was a supernova and death the black hole. She wondered if each man was a little universe, and death a big crunch bringing that universe to an end, while more universes continued to pop out of the quantum foam.

In December, she thought of writing a memoir of her life called Asymptotes: A Memoir of Impossible Passions. She had had four great passions in her life: God, the violin, Aleksei, and Ying. (Later in her entry she amended it to three, crossing out God.) They were asymptotes in her life, lines that a curve approaches but never touches. She could never achieve complete union with them. Her love for them was passionate, often unrequited, dangerous, obsessive, insane. It bridged opposites—beautiful and grotesque, vibrant and deadly, ecstatic and tragic. This love was “the strongest, the sweetest, and the most terrible thing I have experienced.”

On December 2, Alexei vanished again, sending Martha into another depression, with fresh suicidal thoughts. Doing homework was torture for her. I met with all six of Martha’s teachers to negotiate lower homework loads for her.

Martha decided she wanted to play violin again for the first time since smashing the car door on her hand to drop out of music earlier that year. On December 21, we attended Martha’s winter concert—her return to orchestra. She now played second violin instead of first violin, but she seemed happy to be back at all. She resumed playing at home too, as she had before the car door incident. She was conscientious about not playing while we slept, but once everyone was awake, we could hear the sweet tones of her bow at almost any hour that she was at home. She played in the playroom, serenading us with a varied repertoire of classical and pop tunes.

By then, she had amassed a number of fragmentary stories, such as Meadowlake Castle, 894 Bumblebee Lane, The Lost Lake, and Their Parents’ Battles, and she decided to unify them all by setting them in an imaginary country called Logia. Located in the North Atlantic between Europe and North America, Logia was settled by atheist dissenters fleeing Europe in the Middle Ages. She developed a history of monarchies, rebellions, and palace intrigues for the island country from medieval times to the present day, and planned a series of novels that would mark out that history, each with an elaborate plot and many characters. All were tragic love stories rife with passion, betrayal, torture, and death. They allowed her at once to express the overriding concerns of her life and to escape from them into a world where other people suffered whatever she dreamed up for them.

From then until the end of her life, her journals contained pages and pages of fragments of the Logia cycle, usually in the form of internal monologues ascribed to one character or another. For example, in her planned novel Hexagon, a merchant’s wife named Mercedes runs away with a pirate named Felipe. Felipe captures a princess named Penelope and begins to fall in love with her, making Mercedes jealous. This is the beginning of one of Mercedes’s monologues:

Mercedes: Penelope is ruining us. When Felipe looks at me, he avoids my eyes. His eyes sparkle around Penelope and she does not even love him. What a fool he is, throwing away my real love for his infatuation with some princess. In my moments of darkness, I long for his death. Constantly, I long for Penelope’s death.

She made many lists of characters and their relationships and features, such as hair color and eye color; she tinkered with plotlines, titles, chronologies, settings. When she listened to popular songs, she imagined them as sung by characters in her novels, with meanings proper to them. “Sing” by My Chemical Romance was attributed to her character Pura, “Firework” by Katy Perry to her character Rachel. Her characters, she said, were her “vicars. They lived the romantic and morbid adventures I had forbidden to myself.”

Martha’s creative ferment seemed to me to protect her from suicidality like a wall. If only the wall had been higher.

Copyright 2020 George Ochoa.

Write a comment