In September 1999, Martha started kindergarten in the Dobbs Ferry public school system. She would stay in that system for most of the rest of her life.

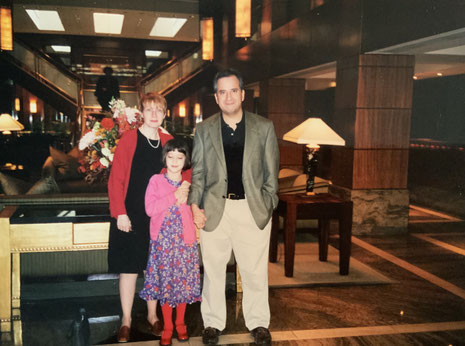

Martha at seven, with her parents, circa 2001

That first day of kindergarten, we were all groggy from lack of sleep. Preschool had been in the afternoon, perfect for late-rising freelancers. But for kindergarten, Martha had to wake at 6:45 a.m. She and the parent on duty had to be out the door by 8:00 to walk around the corner to the bus stop, where the bus picked her up at 8:08.

Aside from having to adjust to the new sleep schedule, Martha slipped easily into kindergarten. I don’t remember much about her from that year, except that we kept taking her to playdates with other children and playing with her at home. The day before Thanksgiving, exhausted from playing, we lay in bed under the covers facing each other and she said, “Daddy, Daddy.”

“I’m so happy to be your Daddy,” I told her.

“I’m happy to be your child.”

And she fell asleep, in one of her rare naps from this period. And I knew what I was thankful for that Thanksgiving: that I had this child, and she loved me, and my mere presence calmed her enough for her to fall asleep. And she was happy, and happy being my child.

Still, it makes me wonder. Martha would later say she had never been happy, yet I have her testimony that she was happy at five. If she was happy, presumably, she wanted to keep on living. She had no deathwish. If, after five years on Earth, Martha had still not developed her deathwish, when did it appear? When did she first begin to think that death was better than life?

###

We continued our practice of rarely using babysitters, so even when we went to a grownup party to ring in the new millennium on December 31, 1999, Martha came along. She got bored by the sight of a bunch of adults dancing to songs like “Dancing Queen,” so we left by 11:30 and rang in the new era at home. The next day, she told her first fully accomplished joke. Having watched South Pacific, she asked, “You know what a beaver sings?”

“What?” I asked.

“‘There is nothing you can name that is anything like a dam.’”

She kept reading and playing computer games, mostly academic ones like Jump Start 1st Grade. She composed a poem, “I Love My Mommy.” I doubt she wrote it with her own hand, because she may not have learned to write yet, but someone at the school typed it for her. In the poem, she listed the reasons she loved her mother. For example, her mother let her do a story with her bath toys in the bath; I did too, but Melinda, less inclined to setting time limits than I, let the story run longer. And when Melinda went into town to get her hair cut she would bring home treats, like sticker storybooks about mermaids or wild animals, which Martha used to tell stories with the stickers. “I love my mommy and my mommy loves me,” the poem concluded.

In April, Martha turned six. By then, almost everyone who met her remarked on how intellectually advanced she was. All they had to do was talk with her. The jeweler at Tiffany’s in the Westchester Mall called her a prodigy.

Since preschool, Martha had been learning ballet at Central Park Dance Studio in Scarsdale, and there, in the summer of 2000, she performed in her first play, The Wizard of Oz. She didn’t have a big role; she was part of the chorus line of Munchkins and Winkies. But she had lines: “The Great Wizard is our ruler” and “Y-y-yes.”

At some point Martha had an accident. While running in the basement, she fell and slammed her forehead into the sharp edge of a dresser. Blood poured and she howled in pain. A doctor in the ER closed up the wound with glue. After that she always had a little scar on her brow. Forever ready to feel guilty, I feared the scar was the result of our not having consulted a plastic surgeon. But it faded over time, and of course it doesn’t matter now.

In fall 2000, Martha started first grade, which is where she probably learned to write. When she was just learning, she wrote us the following note:

Dear parints,

Have a great day.

Love,

Martha

We loved the note so much, youthful misspelling and all, that we pinned it to the refrigerator with a magnet. Over the years it got stained and water-damaged from proximity to the sink, and we finally took it down to preserve it. That was not long before she died, and I wondered if the act of taking it down helped to kill her. We stored it somewhere safe but forgot where, and as of now the note is lost.

In November 2000, Martha first became interested in a presidential election. On the back of a witch poster we had bought her for Halloween, she wrote a sign saying:

Gore!

Lieberman!

Hillary!

We put the sign out front, expressing our family’s support for the Democratic presidential and vice presidential candidates (Gore and Lieberman) and the Democratic senatorial candidate for New York (Hillary Clinton). Gore and Lieberman lost, but Hillary won.

###

My main written source for most of this account of Martha’s life is my journal, which I have kept since 1973, when I was twelve. Unfortunately, there are periods in my life when I wrote very little, and even when I did write during Martha’s lifetime, I sometimes said little about Martha. But after she’d started first grade, on November 6, 2000, Martha started to assist me by keeping her own journal. That Monday night, she decided to use her part with me during the bedtime ritual to have us both write in our journals. Independently, we each described how she had just lost her first tooth the day before, and stuck it under the pillow to get a present from the tooth fairy. The tooth fairy (who I knew to be Melinda, though Martha did not) left her a dollar, a book, and a note that Martha used as a bookmark.

Martha didn’t return to her journal for almost a year, and for many years kept it in somewhat scattered fashion. But in her teen years she wrote in it fairly regularly. While she was alive, I never read any of her diaries, but now that she is dead they provide the best source for what she was thinking and feeling in her last years.

Martha kept losing her baby teeth, and permanent ones grew in. Throughout her life, she never had a cavity—not one. She went to her grave with perfect teeth.

###

During first grade, in January 2001, Martha went on her first and only trip outside the mainland United States, to Puerto Rico. Part of my freelance business had always been medical journalism, and I had to cover a generic pharmaceutical conference there, so I brought Melinda and Martha along. Martha had been riding on planes since infancy, because of our annual visits to see my parents in Florida, so the air travel wasn’t difficult for her. We enjoyed the swank resort and had a nice time on the beach.

In April 2001, Martha turned seven, and by then she had developed her own philosophy. According to ideas she began forming in kindergarten, the whole world, the whole universe was in her heart. All things were inside her. She loved every creature and every thing except badness. God was in her heart too and she felt him there.

That school year, Martha had started Catholic religious education, commonly called CCD, at our parish in Irvington. I had a big influence on her because not only did I model religious faith for her at home, but I was her CCD teacher for four years. She loved to talk theology and philosophy with me, and she became interested in knowing how I prayed. I prayed the standard prayers with her at bedtime—the Our Father, the Hail Mary—but I also had my own homegrown way of praying, which I now showed her. After dinner, when I took out the garbage, I brought her out to the front yard, leaned with her against our car, and looked up at the night sky. I taught her how to feel God’s presence by looking at the things around her, realizing that he made them and that he was everywhere. Then I taught her just to be still and listen to him, and say to him whatever was in her heart.

We kept playing too. Martha went through a Barbie phase where we would each put Barbies through various activities. Mine fought bad guys and each other and pretended to be Josie and the Pussycats. Martha’s were very religious, nonviolent, and good, going to Mass and saving the lives of bad guys. It was more proof to me that Martha was better than I was.

Martha was afraid of bees, bugs, and heights. The insect fear would diminish over time, but the fear of heights persisted throughout her life—ironically, considering the way she died.

She still had the trouble socializing that she’d always had. At recess, she was a loner, hardly playing with anyone but her friend Sadie. She didn’t like tag or the other games kids played in the schoolyard. The other kids were nice to her, she said, but she knew she was different from them, a much better reader and more profound thinker. Even on the level of culture, she liked Judy Garland, not Britney Spears. While her peers were still reading picture books, she had moved on to chapter books, like the Ramona series and Baby Island.

In place of the friends she didn’t have enough of, Martha used her stuffed animals. She often played board games like Pretty Pretty Princess and Polly Pocket with animals taking the roles of the other players. She did this even when she had a human friend to play with. Once Sadie got frustrated and said, “Can we play without the animals?”

Martha kept seeing movies in the theater, like Spy Kids, and plays on Broadway, like 42nd Street. She kept enjoying performing in plays too. In the summer, she joined a new theatrical kids’ troupe, Cagle & Company, that she would act in for years, and played a pirate and a lost boy in Peter Pan. In her home version of the play, she gave herself the lead female role, Wendy, and had the doll of hers who had formerly been named Sad Dog play the fairy Tinkerbell. Soon she renamed the doll Tinkybella and transformed her species from dog to fairy. That would remain the stuffed animal’s name and species until the end of Martha’s life.

###

On September 11, 2001, shortly after Martha started second grade, planes hijacked by terrorists crashed into and toppled the twin towers of the World Trade Center, killing thousands. The smoke from the burning rubble was visible from Waterfront Park in Dobbs Ferry. Not knowing what kind of attacks might follow, the administration at Martha’s school had the school evacuated, with the children taken to a nearby church. There Martha learned something of what had happened, and when she walked in the front door after her mother picked her up at the bus stop, she announced with excitement, “I’m part of history!”

After that, like many Americans, we rediscovered the American flag and started flying it outside our house. I got Martha a little flag, and after dinner every night, as her part of the war effort, she paraded around the house with the flag and sang all four verses of the National Anthem. (I never knew anybody else who knew all four verses.) Sometimes she sang the Battle Hymn of the Republic or recited the Gettysburg Address. At bedtime she prayed, “God, please help our country get through the war.” Martha had learned patriotism.

Oddly, Martha’s patriotism gave her a little trouble at school, and not because people disagreed with it. It was just that she told a few friends that she knew all four verses of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and they told other kids. Soon the word had spread and Martha worried she would seem like she was boasting.

Martha hated having any moral flaw. She tried hard never to get what the teacher called a “strike” for bad behavior, and she never did. Yet her heart was so big that she felt sympathy for kids who did get strikes, like her classmate Maxine. “I do not like the way Maxine is treated at school,” she wrote in her journal. “Too many reprimands and misunderstandings, some that worry me, as if I were Maxine.”

At school, Martha made a friend, Joshua, to whom she remained close for years. Like her, he was very smart and socially awkward. He had an imaginary friend whom he embodied by wagging his finger in a creepy way like the little boy in The Shining. Martha and Joshua played elaborate imaginative games at recess and on playdates. Unfortunately, his scientist parents moved him away to Chatham, New Jersey. We tried to keep up the connection but the sixty-three-mile distance made it fade, leaving Martha with one less ally in her world.

At Christmastime 2001, Martha at seven had her first full-blown existential crisis. Part of it was losing her belief in Santa Claus. Like many parents, we had lied to her about this for years. Why parents think lying to children is ever a good thing, I don’t know, but that’s what we did. She asked us point blank whether it was really Santa who got her presents every year. Melinda gave her a “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus” sort of answer that left Martha unsatisfied. Drawing on Catholic teaching, I told her that Saint Nicholas, the saint, was real, but not the jolly old elf of legend. She seemed glad to get this straightened out, but beneath the surface it appeared to disturb her.

It was the first Christmas that wasn’t pure joy for her. It didn’t feel like Christmas, she said. She cried because I didn’t trim the artificial tree with her as usual that year; Melinda did. She cried because after Christmas she had to take apart the Toyland Town of gifts she’d formed under the tree. She had created a mat of Felt Kids all across the playroom floor, and when I asked her to clean that up after Christmas, she agreed but cried because they would soon be out of sight. She was feeling the transience of things, the irretrievability of things in the past. I read to her Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem “Spring and Fall: To a Young Child,” and tried to talk with her about transience, but I don’t know how much it helped.

“I feel like Rose on her first night of Titanic at sea,” she wrote in her diary, alluding to the movie she had seen as a toddler and that had become one of her favorites. On her first night at sea, Rose had contemplated jumping off the stern of the ship, so this might be considered an early sign of suicidal thoughts in Martha—but if so, she didn’t say so explicitly. Instead she wrote, “I have a heavy load of worries, and every day it is added to. I fear it will topple, meaning I will suddenly cry.”

Soon Christmas vacation ended and Martha went back to school and returned to what seemed like normal. She played with American Girl dolls and made a new nook for herself out of the bed covers on her floor before the bed was made. She learned what thirteen times thirteen is (169) and started coloring with a box of ninety-six crayons. But it’s possible she was never quite the same after that Christmas.

For one thing, we began to annoy her, specifically when we sang or whistled around the house. It kept her from focusing on her playing or studying, but she felt she couldn’t tell us, only her diary. “I don’t have a piece of this house that I won’t be distracted by singing and whistling in!” she wrote.

Even her eighth birthday party in April 2002 was a little unusual. We bought her a big, red bull piñata to be stuffed with candy and broken apart with a stick at her party. The night before the party, she cried because she couldn’t bear to see the bull killed that way. She wanted to keep him and name him Jimmy. So we let her, and Jimmy eventually outlived her. Instead of breaking a piñata at her party, we stood on the deck and rained candy down on the children below. They liked that better than a piñata.

Despite Martha’s emotional volatility that school year, I don’t think she developed a deathwish at that time. But that April, she had her first opportunity to witness death.

By that time, we had moved Melinda’s father John from Baltimore to a nursing home in Dobbs Ferry, and one night the nurse called us to tell us he was dying. All three of us sat by his side as the eighty-three-year-old man breathed through an oxygen mask, his extremities already cold. He couldn’t speak but he held our hands. Martha cried and kissed him and hugged us. The nurses converted a recliner into a cot so Martha could sleep, and while she slept, at about 3:30 in the morning of April 24, he stopped breathing.

We wondered if the sight of death would disturb her, but if it did we couldn’t see it. When daylight came she went to school as usual, and we saw her there later that morning at an animal fair, where we admired the polar bear exhibit she’d made. Mainly the experience deepened my respect for her. At eight, she had seen death and taken it in, and it was one more part of the whole world that was in her heart.

In May, Martha had her first communion—“It was the best day of my life!” she told her diary—and she spontaneously started saying grace before meals. That prompted us to start saying grace too, at least before dinner. We keep up this practice now even though Martha’s gone.

While Martha looked to the eternal, she also looked to earthly life, developing a writer’s gift for observation. One day she sat and watched cars passing by on Ashford Avenue, describing them in her diary. “This red one looks silvery, that one’s probably speeding, this one sprouts music, that one’s antenna’s bending.”

That summer I took Martha to the theater to see Star Wars Episode II: Attack of The Clones, part of the series of Star Wars prequels George Lucas was making at the time. The prequels are widely reviled, but Martha and I loved Attack of the Clones, and it prompted her to want to see the entire series as it stood at that time. So we watched the original Star Wars and its two sequels, and the first prequel, The Phantom Menace, making her laugh at how annoying Jar-Jar Binks was. Out of a piece of a cardboard box, we created an original board game, the Ultimate Star Wars Game, on which pieces progressed through a combination of rolling a die and tossing a coin, with two decks of wild cards, Jump to Light Speed and Will of the Force.

She saw Lawrence of Arabia for the first time that summer, ate ice cream at a new ice cream parlor, and acted in another play, Darn Yankees (so called to avoid the profanity of Damn Yankees). She played a newsboy, a baseball player, and a housewife. She seemed to be enjoying life, but I remembered her recent existential crisis and wondered if anything like it would come back. It did, soon.

Copyright 2020 George Ochoa.

Write a comment