Martha now lived in the house and village where she would live until the night before she died.

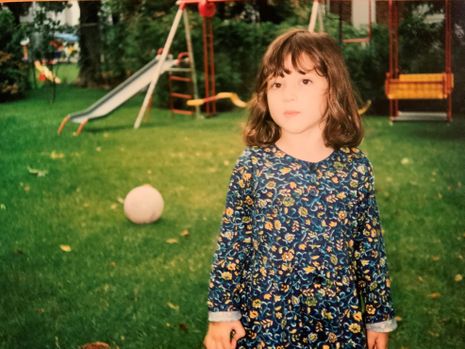

Martha at three, in 1997, in her backyard in Dobbs Ferry

Located on the Hudson River, Dobbs Ferry in 1996 was a picturesque community of 7,000 people, with lavish houses for the rich on the hill and more modest abodes for people like us along Ashford Avenue, the main drag. We lived in a cape colonial with white aluminum siding and a white picket fence. Downstairs it had one bedroom for Melinda and me and one for Martha. Upstairs was a third bedroom that we converted into an office for our home business, Corey & Ochoa.

Martha’s bedroom walls came decorated with a row of paper teddy bears near the ceiling. She had her own built-in bookshelves full of picture books, two windows looking out on the deck and backyard, and a poster of Peanuts characters—favorites of Melinda’s who had become favorites of Martha’s too. Martha still slept in a crib, but we soon converted it into a bed that she could climb in and out of herself. In the morning when she woke she padded into our room next door and kissed the cheek of the parent who was on duty with her that morning. She always knew whose turn it was, and had learned the phrase on duty. Melinda and I worked late into the night, often past three a.m., so I was invariably groggy when I got Martha’s kiss at about eight or eight-thirty. But I was always happy to see her.

Except one morning. That morning, after I had gone to bed around four-thirty, she inexplicably kissed me awake at five-thirty. “Martha, it’s too early!” I told her. “Go back to bed!” But she was up and there was nothing I could do. I groused my way with her into the living room, a scholarly-looking place with our three tall bookcases from Brooklyn, a new green tropical flower sofa, an Oriental rug on the pine floor, and a striped red armchair that had become my favorite place to sit. I looked with pain at the sky just starting to lighten through the Venetian blinds. “Martha,” I said, “if we have to be up this early, I’m going to show you something.”

She trotted by my side, both of us in our pajamas, onto the front lawn of the house. Ashford Avenue was usually busy, but at that hour traffic was still sparse. I took her to the east side, by the white plank fence that separated us from our neighbors, and pointed across their lawn. “Look,” I said.

The sun came up through the foliage of Dobbs Ferry, over the little houses, burning clean and red. As the daughter of two night-owl writers, Martha at two had never seen a sunrise. She watched in fascination, and I watched her, happy to share it with her. I was so proud of her for forcing me into it that when we went inside our small, square dining room, instead of the cereal-and-milk breakfast I usually made her, I whipped up a big stack of pancakes with butter and syrup.

In our first years in Dobbs Ferry, there were many firsts with Martha. She had seen children’s movies in installments before, but the first grown-up movie she ever watched all the way through in one sitting was My Fair Lady, shown on TV in a three-and-a-half-hour time slot on Thanksgiving 1996. It was the first musical she ever loved, and she already knew the music—I had been prepping it for her by playing the record in the basement. She saw herself as the flower girl Eliza Doolittle, me as Professor Henry Higgins, and her mother as the housekeeper Mrs. Pierce. By then Martha had a collection of small plastic toy characters, animals and people, Pooh toys and Charlie Brown toys, who lived in the living room in a clear plastic cabinet designed to hold screws and nails, and she used them to play her own game of My Fair Lady by the fireplace. (We never lit the fireplace, but the brick floor in front of it was a good stage for Martha’s games.) She loved the lyrics, especially “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man?”—“Why can’t a dog be more like a cat?” she retorted mockingly. At night Martha and I danced on the front lawn under the stars while we sang the entire score.

Other movies followed. Her first movie in a theater was Cats Don’t Dance, a mediocre cartoon that she renamed Cats Do Dance because actually the cats danced. I introduced her to Bogart and Bacall with To Have and Have Not. For a while, she was on a Sound of Music kick, imagining herself as the teenage Liesl, her mother as the governess Maria, and me as the Captain. The identification was so strong that when we introduced her as Martha to neighbors or waitresses, she corrected us and said, “No, Liesl!” The same toys that had lately been My Fair Lady characters became Sound of Music characters. Her Linus and Lucy figurines became Rolf and Liesl; her dollhouse became the Von Trapp mansion. Again she memorized the entire score, and played the record and movie over and over.

She went through phases when she favored me, wanting more of my company and less of her mother’s, and others when she did the reverse. It may have been tied to whatever movie reigned in her imagination at the time. When the star was Rex Harrison, she wanted more of me; when the star was Julie Andrews, she wanted more of Melinda. Also involved was her growing understanding of family relations. Mothers were like Julie Andrews, fathers like Rex Harrison. Martha had been visiting her grandparents since she was a baby—Grandpa Corey in Baltimore; Grandma and Grandpa Ochoa in Florida. But only now did she seem to grasp what relation they had to her parents. Her parents, she now understood, had once been children like her, being raised by their parents—her grandparents—just as her parents were now raising her. And one day she would grow up into a lady and she too might become a mother, raising her own child.

She lay on the tiled floor of our narrow kitchen, looking up at me as we discussed all this. “When you grow up and become a lady,” I told her, “maybe you will marry a man.”

She looked straight at me. “You will marry me.”

In Martha’s reversed pronoun speech, this meant, “I will marry you.” I remembered telling my mother something similar in early childhood in my kitchen in Queens, that I would marry her. I recognized both incidents as cases of Freud’s observation that a heterosexual child’s first sexual attraction is always to the parent of the opposite sex. It pleased me, though of course I answered, “Well, not me, but some other man.”

###

For the most part, though, Martha didn’t dwell on the future. She had too much to do now. She formed her toys into worlds and made up stories about them. The toys’ names were always changing. Sad Dog, who by now had switched sex from male to female, was renamed Happy Dog, and then Happy Puppy. She made up poems and songs too, sometimes with nonsensical lyrics, often rhyming or with an iambic beat.

As a writer, I knew that all this storytelling and song-making activity was the beginning of being a writer. Even in my reference books, I told stories about one thing or another—science or the Victorian age. I did the same thing in the novel I was then trying, and failing, to sell, Stranger Still. It was the story of a psychotic college kid who mistakenly thinks a girl he sees in the library is in love with him; when he sees her with her boyfriend, he embarks on a campaign of terror and revenge to destroy the boyfriend. I had never sold a novel, but this was my best one, and our agent in Chicago was trying hard to sell it. So far, she had had no success, but I hoped it was just a matter of time.

Meanwhile, I took satisfaction in Martha. She was the most verbal two-year-old I’d ever seen, and her language was developing swiftly. She verified Chomsky’s theory of generational grammar by saying phrases we’d never taught her but that she constructed using rules she would need to modify later, such as “Take off it” or “Cut up it,” which she generated through inference from the prevailing object placement rule.

As soon as she learned to ask questions she looked constantly for knowledge. When feeding her toy giraffe, she asked, “What do giraffes like?” “Leaves,” I answered. When we danced to my Beatles records, she asked, “Do you know their names?” “John, Paul, George, and Ringo,” I answered.

Nature interested Martha. We put up a bird feeder to try to attract birds, but they didn’t seem to notice. So we marched around the backyard, making up a song to get their attention:

Woodstock, come get your food,

Woodstock, come get your lunch.

Woodstock, it’s time to eat today.

We said Woodstock because we knew that bird from Peanuts. In subsequent verses, we substituted birds’ names from other sources: Big Bird from Sesame Street and Zazu from The Lion King.

The birds never discovered our feeder, but we spotted some elsewhere. In the spring a pair of robins built a nest under our deck. Day by day we watched as the mother laid eggs, the eggs hatched, chicks sprouted. The red-breasted father shrieked at us violently when we came near to peer at the young ones, but we didn’t want to harm them, only admire them. Soon the young robins flew away, and Martha applied the lesson to herself. “You be a lady soon,” she said about herself. “Yes, Martha, all too soon,” said her mother.

Martha often argued with us, sometimes quite philosophically. If we pointed to a tree and said it was a tree, she’d say, “No, it’s not.” We’d say, “What do you think it is?” She’d say, “Another tree.” We’d say, “Another tree is a tree.” This was easy to assert but hard to prove.

She made quick progress toward reading. By December 1996, at two, she had learned the whole alphabet and figured out that letters strung together are words, and that a printed word, like apple, “says” apple while a picture of an apple is a “picture” of an apple. By around her third birthday, in April 1997, she had learned to identify some words by sight—cat, Martha—and was beginning to grasp phonetics, the idea that l makes a “leh” sound, t a “teh” sound.

She added for the first time while we were on a road trip to see her grandfather in Baltimore. She counted two female tollbooth attendants plus her mother as three women, and one male attendant plus me as two men. “Five people,” she said.

She developed an aesthetic sense. When choosing an animal vitamin in the morning, while wearing a purple sweater, she said, “Today you need a purple bear ’cause you are wearing purple and you also need a purple bear. Tomorrow you will be wearing pink.” When we headed out to dinner one night, she wanted to change into dressy clothes, saying, “I can’t go out like this!”

We painted with watercolors in the basement, but otherwise Martha didn’t show unusual interest in visual art. And aside from dancing, physical activities held little appeal for her. Swinging on her red and yellow swing set in the backyard was okay, but throwing a ball bored her. I bought her a tricycle for her third birthday and she never learned to pedal it. She went to her death without ever even having tried to ride a bicycle.

I don’t think she ever fully learned to tie her shoelaces. Once she got old enough to choose her own footwear, she always wore slip-on shoes, like Keds. And although she did learn to swim once, as a small child in her grandmother’s pool in Florida, she forgot later on.

In the category of physical activities that she didn’t want to bother with, a prominent example was using the potty. She liked wearing diapers and saw no need to give them up. We, of course, felt otherwise. When she was two, we started showing her a video about a little cartoon girl learning to use her potty. She loved this video, especially the afterword by a live-action pediatrician, which was intended only for parents. But she was slow to apply the video to action. Only in December 1996 did she start sitting on her potty, without depositing anything into it. Not until she was three, in August 1997, did she start doing number one into it, but not number two. Not until her fourth birthday did she finally master the toilet and give up diapers entirely.

Throughout that time, we applied gentle pressure, but didn’t rush her. We weren’t the type to rush Martha into anything. We had a soft way of getting things done. For example, we found a church in the nearby village of Irvington we liked, with a Mass in the evening (we hated waking up for morning Mass). The church had a cry room where Martha could play and chatter all during Mass, and sometimes she accompanied us there. But if she didn’t want to go, just one of us would go to represent the family. Eventually Martha herself got to like the idea of going as a family, and wanted to sit up front instead of in the cry room. So gradually we became a full-fledged churchgoing family.

Our softness extended to corporal punishment. We never hit Martha, not once in her entire life. In those early years, I was proud of this, and bragged about it to a friend of mine who believed in spanking. He argued that spanking was necessary for a child’s healthy development; I said we would watch Martha’s development and find out. Well, for all I know he was right. He raised a son who is still on earth; I raised a daughter who put herself in the grave. I am not able to point to anything I did as a parent and say for certain it was the right thing, since the result was so terrible. Yet I’m still pleased I never hit Martha, because my father hit me as a child and that is among my worst memories, and at least I know Martha went to her death with no such memories.

Even though I never hit Martha, I did use force on her occasionally, for example, to wrestle her into her pajamas when she opposed going to bed. I had certain rules, such as that I would never give into a demand of hers while she was crying (unless she was crying from pain). We could negotiate until she started crying, but I didn’t want her to think that she could use tears as a wringer to make concessions drip from me.

Another rule I had her live by was that health and safety came first. If she didn’t want to go the doctor or resisted holding my hand when crossing the street, I would inform her that this was a matter of health and safety, and that overrode all other considerations. She got used to this idea until she was a teenager, when she staked her life in rebellion against it.

I tried to encourage in Martha a strong moral sense. On long car trips to Baltimore, where we had to help Melinda’s disabled and widowed father, who was transitioning from a live-in health aide to a nursing home, Martha would sometimes get restless, and I would calm her by saying, “We’re doing this to help Grandpa.” I always kept my promises to Martha and taught her to keep hers. Melinda was more of a soft touch, and as a result Martha tended to be more whiny and manipulative with her, so that Melinda sometimes used me as the disciplinarian of last resort—“Otherwise I’ll call Daddy.”

If Martha got seriously out of hand (which she did sometimes), I would give her a time-out, with the time based on her age—two minutes when she was two, three when she was three. She sat crying on a stool in her room during these punishments, while I sat nearby. But that was rare. She hated time-outs because she was a perfectionist and didn’t want the smear on her moral record, just as she would later hate to get anything but A+’s in school. Her last time-out—her last punishment of any kind—came when she was six. After that, she tried hard never to do anything wrong.

###

Martha was overall a happy child, not much given to crying or fussing. But like anyone, she had feelings that weren’t always pleasant. I told her nobody could feel her feelings but her and taught her to talk about them. For example, she told me that she was scared of using the potty, and that when she didn’t get her way she wanted to cry.

But there was something more about Martha, even at three, something I couldn’t quite identify and that she didn’t put into words at the time. It was a look on her face, a sound in her voice that seemed to indicate her awareness of her aloneness. Martha had great fun with her mother and me; we had a ball. But she had few friends her own age. As a baby, she’d had playdates with a pair of young girls who lived in our building in Brooklyn, and she played with a few children in Dobbs Ferry. But those children too seemed to come in pairs—the Wortner boys, sons of an old high school friend of mine who lived in Dobbs Ferry; Amanda and Brittani, two girls next door; the Rottersdam girls, whom we met in the park. Everywhere other children had siblings, which gave them a social knowledge Martha had not picked up, and strength in numbers. Martha hardly knew what to do with them or how to play with them. In playdates, she often played separately from them. The parental advice books I read told me such parallel play was normal in early childhood. But those fleeting looks of loneliness on Martha’s face haunted me.

Martha had two young cousins in the neighboring village of Irvington, and maybe if she had played regularly with them, that would have helped her socialization. But in 1996, I had a terrible fight with their mother—my older sister, my only sibling. As a result, she and I weren’t on speaking terms and the families couldn’t mingle. We stayed at war for nine years, until she made a peace overture in 2005 that I accepted, allowing the families to reconnect. By then it was too late for the cousins to be of much help to each other. Like all wars, it was a stupid waste of young lives, mainly Martha’s.

While Martha was still three, Melinda and I talked about maybe having a second child. Melinda resisted because she thought we had a nice-sized family already, and she had been an only child and had turned out all right. But I had grown up with a sister and considered two children to be standard. And I was fearful of putting all our eggs, so to speak, in one basket: what if something happened to Martha? Then too, maybe having a second child would help relieve Martha’s loneliness. Melinda eventually agreed to try for a second child, but we didn’t start trying until Melinda was forty-one. Very likely that was biologically too late for her, and our efforts failed. Martha remained an only child, and struggled socially all her life. And when we lost her we were childless.

Chapter 3 of the memoir AFTER MARTHA.

Copyright 2020 George Ochoa.

Write a comment