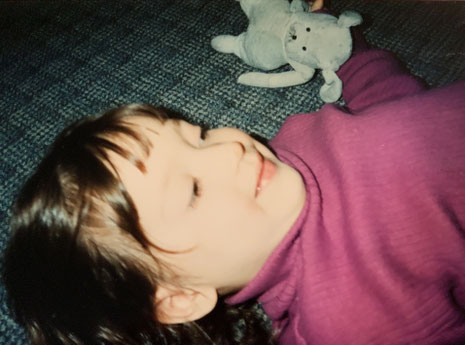

By the time Sad Dog became her chosen stuffed animal, Martha had developed a definite personality. Melinda and I called her “gentle and intense.”

Martha at two, with Sad Dog, in 1996

She was a sweet, good-natured child, more likely to be smiling and pleasant than crying or fussing. But when she got interested in something, she focused on it and hung on intensely like a dog with a bone. She sat and turned every page of a picture book, then picked up another one and turned every page of that. If I needed a few minutes to do a chore, all I had to do was hand Martha a deck of cards, and she would be occupied for a while, turning over every card in the deck individually to inspect its front and back. We had a bookcase designed for paperback books, and Martha emptied its bottom shelves, studying the covers of each book one by one. She crawled around the apartment, carrying 1984 in one hand and The Communist Manifesto in the other. It was a railroad apartment, where one room led to the other with no intervening halls, so I could stand at one end in the kitchen and watch her trundle toward me across the plank floors with her books all the way from the far end in our bedroom.

Since Martha was born to a couple of writers, it made sense that from infancy print fascinated her. Martha’s toys and books littered the apartment, but she almost always chose a book over a toy. Her mother kept a wooden rack full of catalogs, and sometimes Martha would read those, flipping pages of children’s clothes from Hanna Andersson or women’s dresses from Saks Fifth Avenue. That was where, in March 1995, she first learned to stand unsupported—standing beside the rack, flipping through a catalog, like a customer at a bookstore.

Around that time, at eleven months old, Martha made a great intellectual leap. While she sat on my lap and I showed her a Reader’s Digest with a cover picture of a baby leopard, she said, “Kaah.” I knew she was saying cat, her first word that wasn’t Dada or Mama. This alone was a milestone, but what startled me was that the baby leopard didn’t exactly look like a house cat—it was thicker and wilder. Yet Martha had correctly identified the felineness that made it like a cat. She had spotted not the species or even the genus but the family. This seemed to me to suggest a remarkable mind, able even at that age to look deep within things and discern their underlying structure.

From then on, Martha talked. Her pronunciation was delightful—straining, foreign, determined, always met with heaps of praise from us. Sad Dog she pronounced “Ad-Daw.” She heard us imitating our agent, who, when we were worried about a book deal, liked to say, “Trust me”; Martha made it “Truh.” Within the next few months, by the time she was eighteen months old, she amassed a vocabulary of at least 152 words. They included cookies, flower, dinosaur, diaper, work, bye-bye, and all done.

By then, Martha was walking—she picked that up shortly after her first birthday—and looked less like a baby and more like a young girl, with a full head of wavy brown hair. She was more beautiful every day, clothed in bright dresses carefully selected by her mother. Her mind, too, grew more beautiful. She learned to count, to say “Two” when she saw two bears on a page. She learned sentences, such as “Dada play Martha”—a plea for me to play with her instead of working. She became enthralled with sorting things, the beginnings of her lifelong interest in classification. She would go through every last item in a cabinet or drawer, organizing them in mysterious piles on the floor, carrying them from room to room.

Morally, she developed too, principally by learning the word no. This is essential to a life of human choice. Yes is the underlying stratum, but without no it expresses mere infantile passivity. Once Martha learned no, she used it all the time, insistently and powerfully, rejecting one food in favor of another, one book for another, one activity for another. Through her nos, Martha exercised her will the way walking exercised her legs.

She learned goodness too. With great tenderness, she had her toy animals kiss each other. She fed them, gave them tea and books. I told her, “Bunny is tired. Can you rock Bunny to sleep?” She clutched the bunny close, rocking her. She never hurt her animals, only gave them good things. She had never seen anyone hurt another being, and it wasn’t in her to dream that up.

In April 1996, Martha turned two, and her nature continued to be noble. I heard from other parents about how their two-year-olds were difficult, mischievous, and rebellious. Martha had days like that, but mostly she was eminently generous, patient, and rational. If I listened to her, she would tell me what she wanted. If I asked her to wait, she would wait. For example, if I needed her to wait to play for a few minutes while I finished up some work, she’d wait, then say, “All done work, now play Martha.”

We were a Catholic family, and by the time Martha was two we took her to church on Sunday. She had trouble keeping quiet and couldn’t make much sense of the Mass. But even then she was a spiritual girl. After dinner, she would say, “Take garbage down, look at moon.” All three of us would walk down the two flights to the stoop, deposit the garbage in the pail, then sit on the stoop and look at the moon. If we couldn’t find the moon, she’d say, “Moon hiding,” and we’d look for it another night. Contemplating the sky and its objects, I think, is the first step toward religion: the first moment when you see there are things greater than you that have no practical value, yet you want to reach them. You can’t reach them, but you can commune with them.

Martha was running by then, though not yet jumping, and using pronouns, though with a little confusion. Because we always referred to her as you and to ourselves as I, she did the same, saying, “Dada get your bath ready” when she meant “Daddy is getting my (Martha’s) bath ready.” She worked this out in time, and learned to jump too.

In July, Melinda and I bought a house in Dobbs Ferry, a village in Westchester County, New York, a few miles north of New York City. We were still chronically insolvent, with no money of our own for a down payment, but Melinda’s father had saved some money from his years as a driver’s ed teacher, and that funded the purchase. Now that Martha was bigger and more active, our apartment in Brooklyn seemed too small, and we wanted to give her what we’d both had as children, a backyard. Also, we were already thinking ahead to Martha’s schooling, and we wanted to live somewhere with a good public school system.

On the day of the closing, I drove Melinda and Martha home from the bank in Westchester and parked the car in front of our Brooklyn apartment building. Melinda held Martha in her arms while I got packages out of the trunk. Martha inquisitively stuck her right pinkie into the trunk. I don’t know if Melinda was distracted by the stress of the day, but she didn’t see what Martha was doing and slammed the trunk onto Martha’s finger.

Martha howled. We carried her upstairs and put ice on her finger. It was bruised and bent and we should have taken her to the emergency room, but for some reason we didn’t. The next day we got around to taking her to the doctor and having her finger X-rayed. Sure enough, it was broken. Not only that, but the break was jagged; it wouldn’t heal properly without surgery. At two, Martha would have to have an operation.

I wasn’t praying much in those days, but the night before the operation, I said a rosary—fifty-three Hail Marys and six Our Fathers. I was worried about many things at that time—the house we’d just bought; the huge mortgage payment we’d have to make every month; leaving New York City; the money we weren’t making; the novel of mine, Stranger Still, that wasn’t selling; the literary fame I didn’t have; the spreading gray in my hair. But as I prayed, I realized all of that was small and unimportant compared to Martha’s littlest finger. All I wanted was for Martha to be well and whole. She had become the center of my life.

Dr. Howard Levy, the top hand specialist at Beth Israel, operated on her while she was under general anesthesia. He realigned the parts of the broken bone and pinned them together without having to make an incision. She emerged from anesthesia on my lap in postop, crying, hysterical, in pain, with a snowy cast from her elbow to her fingertips, an IV hooked to her left hand. Gradually we calmed her, but she couldn’t go home until she drank fluids, which she refused to do. At that time, she had just discovered the first movie she ever liked, Babe, a story about a pig who herds sheep, which we played regularly for her in short installments on the VCR. In one scene, Babe the pig is disconsolate, refusing to drink and in danger of dying. The farmer persuades Babe to drink by singing him a song that begins, “If I had words to make a day for you…” I sang the song to Martha, and she remembered and drank.

Martha’s arm was still in the cast when we moved to Dobbs Ferry on August 3, but by then she paid no attention to the cast, playing and reading and laughing as if it wasn’t there. Late in the month, Dr. Levy took off Martha’s cast, inspected her pinkie, and said, “Beautiful.” The X-rays showed it had healed correctly. I gave thanks to God and Dr. Levy and modern medicine for rescuing my daughter’s finger. It grew perfectly throughout her childhood.

But I had to wonder. Why had we waited a day before getting Martha to a doctor? As it turned out, it made no difference, but we didn’t know that then. Why the hesitation about going to the emergency room? I couldn’t explain that, any more than I could explain why we hadn’t noticed Martha sticking her finger in the trunk. Parents are not gods; they’re human, and humans make mistakes. After that, we were much more careful, always telling Martha to stand back when the trunk was about to close, doing an “all clear” before shutting it. But Martha would one day develop a much more serious problem, and at least one more time when emergency action was called for we would hesitate. And that time there would be no Dr. Levy to save her.

Chapter 2 of the memoir AFTER MARTHA.

Copyright 2020 George Ochoa.

Write a comment